Survey Period: 2009-2013

Reaching Out to the Community

We developed a list of survey questions and began contacting people in August of 2009. Concurrently we began announcing the project to the community, so that when potential participants received a phone call they would have already heard of the project. Over the next three years, we used the following methods to identify and reach out to potential participants:

- Announcements through church newsletters and local newspapers

- Radio reports and newspaper articles about the project

- Booths at public events such as art fairs and Relay for Life

- Search of public death records, then obituaries to identify next of kin

- Search for next of kin contact information through Whitepages.com and phone books, then outreach to people by phone, letter, or email

- Word of mouth: people that were contacted about a person with cancer would name others

- Online social media and an online survey

Whitepages.com was a valuable source for addresses and phone numbers. During our survey period in 2009-2013, we were in the “sweet spot” moment where Whitepages was still free and people still had landlines and didn’t have Caller ID! We always felt anxious while making these calls, but we were relieved when most people welcomed our calls, chose to participate, and volunteered names of others from the White Lake area that had been diagnosed with cancer.

Family members that did not return phone calls or did not respond to letters were assumed to have declined to participate and their family members’ names were removed from the list. Approximately 100 letters, phone calls, or emails did not receive a response. Overwhelmingly, however, we discovered that people wanted to participate and wanted to talk about their cancer or the cancer of their loved one. They wanted to tell their stories.

Criteria for Inclusion

No one was included in this project unless they completed a survey or a family member completed a survey on behalf of a person that was deceased or otherwise unavailable.

We included people who had grown up in the White Lake area but had moved away before being diagnosed with cancer.

After seasonal residents expressed concerns about their own cancers and cancers of their fellow vacationers, we included seasonal and part-time residents. This extended to situations such as children whose parents had shared custody, and teachers and students who were away during the school year but returned to the White Lake area during the summers.

We included individuals who had been born as early as 1910, which would provide a comparison of our community’s cancer incidence over time, through three to four generations.

The following Criteria for Inclusion were posted for individuals wanting to complete a survey.

- Participants must have had cancer: all primary cancers, not cancers metastasized from another site, were included. (Non-metastatic basal and squamous cell skin cancers were included initially but later removed, although melanoma and metastatic skin cancers remained.)

- Participants must have been born 1910 or later.

- Participants must have lived (full time or seasonally) in the White Lake area for at least one year prior to their cancer diagnosis, or must have worked in the White Lake area.

- Participants or their family member or loved one must have completed a survey, thereby granting permission to be included.

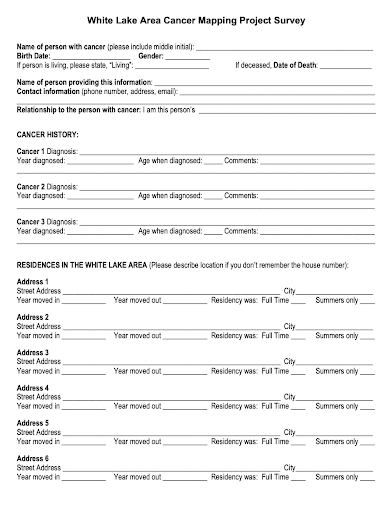

The Survey

The population of the White Lake area in 2010 was approximately 94% white, so we did not include a question about race in our survey. Almost all of our participants were white.

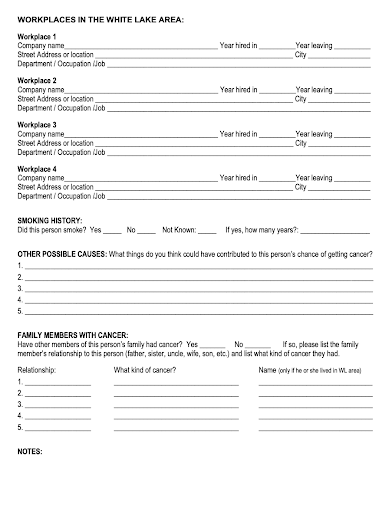

Below is the final version of the survey, revised February 11, 2011. The original 2009 version did not include questions about workplaces. In 2010, after learning that some of our participants had worked at foundries in Muskegon and upon advice from the county health department, we added a request to list all workplaces, within and outside of the White Lake area. We also added questions about family members with cancer.

We had been reluctant to ask about smoking on the survey because we did not want to be intrusive, but after many people volunteered the information that they or their family member had smoked, we revised the survey again in February 2011. In this final revision, we also limited our workplaces question to those sites in the White Lake area, and on the advice of our Muskegon County epidemiologist, we added the question, “What things do you think could have contributed to this person’s chances of getting cancer?” This allowed people to mention their out-of-area workplaces, as well as any other exposures.

Organizing and Recording the Data for Confidentiality

As the coordinator of the Health Committee, it was my responsibility to set up the master spreadsheet and transfer data from the completed surveys. I received guidance from the Muskegon County Health Department regarding confidentiality and how to organize the data for analysis. Before turning data over to the health department, all names and identifying information would need to be removed.

I assigned an identification (ID) number to each participant, and instead of listing dates of birth, diagnosis, and death (if deceased), I listed only the year of birth, diagnosis, and death. I recorded full addresses on the spreadsheet because they would be needed for geocoding. Other information from the survey that was recorded on the spreadsheet included names of workplaces, relationships of relatives with cancer, and codes to note whether the family member with cancer had also lived in the White Lake area. Names of family members were not recorded on the spreadsheet: if the family member was also a participant in this project, I recorded their ID number so that connections between family members with cancer could be made without revealing their names.

Limitations of this Cancer Mapping Project

I want to be clear that there are many limitations to a retrospective, voluntary, self-reporting survey. In a situation such as ours, in which the industries had shut down and the threat to human health was largely in the past when the cancer concerns emerged, a citizen-conducted health survey with the purpose of determining connections between exposures and cancer might not be the best use of the volunteers’ time and efforts.

On the other hand, if the community is still experiencing pollution and citizens’ attempts to get help from government entities are failing, the purpose of the survey or neighborhood canvassing project might be to persuade public health officials to conduct a formal study with the goal of stopping the pollution. In this case, residents need to try every possible course of action. The collection of health data, combined with air and water monitoring data and residents’ personal logs of their pollution experiences are some of the tools that citizens can use to fight for their right to clean air and water.

Below are some of the challenges and limitations I encountered.

- My lack of expertise in epidemiology and statistics and my limited ability to fully understand much of the research I consulted could have led to some inaccurate assumptions.

- The volunteers on our Health Committee did not receive formal training in statistics or in conducting surveys. This could have led to incomplete or inaccurate information being recorded as well as bias.

- The number of participants in a voluntary, self-reporting survey would be expected to be a small percentage of the actual numbers recorded by cancer registrars. People must first hear about the project and then choose whether or not to participate.

- A voluntary, self-reporting survey can result only in raw data. Without information such as the age, sex, and population characteristics of the community surveyed, it is not possible to analyze the results.

- Retrospective information-gathering is cumbersome and fraught with possibilities for error. Participants on this list had been diagnosed with up to four primary cancers, had lived at up to six White Lake area residences, and had worked at up to six White Lake area workplaces. Participants struggled to remember what year they moved from one home or workplace to another.

- There seemed to be many more participants having been diagnosed with cancer in recent years. Because these data were obtained through a voluntary survey, this could have been an impression of a surge in cancer cases in the 2000s rather than an actual surge.

- Geocoding accurately is a challenge. I used online tools to geocode the addresses, then checked the geocode locations, correcting inaccuracies when they occurred. Older address books sometimes listed only Rural Route numbers. Sometimes a survey respondent could not remember an address but could provide a street name and describe the location of the house. I would drive to that location to obtain the address.

- We did not include a question about participants’ smoking history in our survey until February of 2011. Although some survey respondents filling out surveys before then volunteered the information that the person had smoked, we have incomplete smoking histories for surveys completed prior to February 2011.

- Our survey was both too broad (all cancers, over a century of time) and not broad enough (for example, we included workplaces, but didn’t think to include schools, where children spent a large portion of their time, occasionally being sent home from school due to a toxic release).

As I organized data for presentation in the tables, charts, and maps in this report, I checked and rechecked the numbers repeatedly to be sure they were as accurate as possible. I also went to great lengths to avoid bias. Nevertheless, please keep in mind that the numbers are simply cancer counts, without analysis and without the ability to draw statistical conclusions. That said, I believe they hold some truths and make valid points in our efforts to connect the dots between hazards and cancers.