Area of Concern: 1985-2014

Evolution of Industrial Pollution Laws

I have often thought that this cancer mapping project might not have been necessary if industries of the mid-20th century had been required to prove that their chemicals were safe before proceeding into mass production and then convenient disposal of their toxic wastes, or if government entities had existed that would have intervened when these polluting events occurred. Many of the environmental laws evolved during (and in response to) the period of chemical pollution that began around the 1950s in cities and towns across the United States, including in the White Lake area.

The Federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Clean Air Act were not formed until 1970, with the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) following in 1974.

For more information on federal legislation, see Arthur C. Stern & Emeritus Professor’s History of Air Pollution Legislation in the United States, and the EPA’s Evolution of the Clean Air Act, History of the Clean Water Act, and Overview of the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Michigan’s Toxic Substance Control Commission operated from 1978 to1989, when it was transferred from the Department of Management and Budget to the Department of Natural Resources.

For a summary of Michigan citizens’ attempts to address their air pollution concerns, see Air Quality Politics in Michigan [1950s-1970s] created by “Michigan in the World” and the “Environmental Justice History Lab” projects of the University of Michigan History Department.

For additional information on Michigan’s water protection programs in relation to citizen concerns in the White Lake area, see Cost-Efficient Contamination [Trost, 1981]. The full story is very telling of industrial chemical disposal in the 1950s, and a few excerpts are as follows:

“In the 1950s, Michigan’s Water Resources Commission was chiefly responsible for monitoring industrial discharges and enforcing the few laws against pollution that existed. The commission was formed in response to the state’s Water Pollution Control Act of 1929, a broad and weakly-enforced law which basically forbade the discharge of harmful things to surface and groundwater.” The agency, together with the Department of Natural Resources, had “acted more as consultants than cops and, in the end, the regulators were regulated by industry itself.”

“The Water Resources Commission granted Hooker its original waste disposal permit in December of 1952.”… “It was not until 1976 that the state threatened to revoke Hooker’s waste discharge permit because of illegal discharges of C56 into the water and air. The company had been spewing 10 pounds of C56 a day to White Lake.”

It would take years of trial and error before federal and state entities became positioned to begin enforcing the laws.

White Lake Becomes an Area of Concern

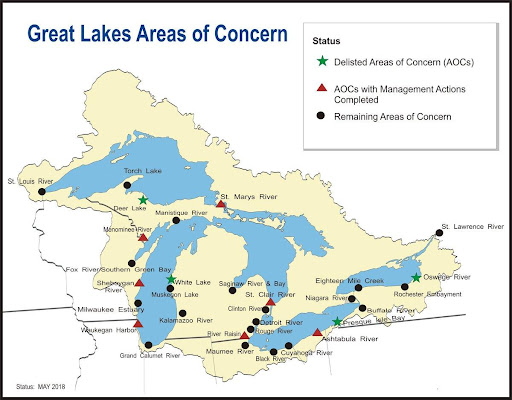

Areas of Concern Map 2018, Great Lakes Now

In 1985, White Lake was listed as a Great Lakes Area of Concern (AOC). Industries located around White Lake had polluted the groundwater, surface water, and air during the early- to mid-20th century, prompting federal, state, and local entities to work together to try to end hazardous production and discharge practices and to see that the contamination was cleaned up.

In 1909, the Boundary Waters Treaty, a bilateral agreement between Canada and the United States, was created to prevent and resolve conflicts over shared waters. The International Joint Commission (IJC), consisting of representatives of the United States and Canada, began meeting in 1912. The IJC recognizes that each country is affected by the other’s decisions that impact water quality, and works to protect the lake and river systems along the border.

Scientific studies conducted by the IJC led to the 1972 signing of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA), a commitment between the United States and Canada to restore and protect the waters of the Great Lakes. In 1987 the GLWQA identified 43 of the most polluted locations as Great Lakes Areas of Concern: 26 in the United States, 12 in Canada, and five shared between both countries.

White Lake was one of 14 AOCs listed in the State of Michigan. Although several sources of the contamination of White Lake were later identified, the primary cause behind adding White Lake to the AOC list was the discharge of contaminated groundwater to the lake from the Occidental (Hooker) Chemical Company property.

Chemicals produced at Hooker Chemical included gaseous chlorine, sodium hydroxide, and hydrogen gas. Hooker received national attention for its production of C-56, Hexachlorocyclopentadiene, a chemical associated with the powerful pesticides Kepone and Mirex, from 1957-1977, and its disposal of C-56 wastes by dumping them into lagoons onsite or placing them in 55-gallon drums. Twenty thousand drums were later found on Hooker’s property, having been cut with axes to allow the wastes to leak into the ground.

Powerful descriptions of what took place may be found in two award-winning reports: Cost-Efficient Contamination [Cathy Trost, 1981, The Alicia Patterson Foundation] and White Lake Moves Beyond its Toxic Past [Jim Lynch, 2014, The Detroit News].

The history of Hooker Chemical is also detailed in chapters of two books on restoration and recovery after environmental degradation, written by John J. Berger (1987) and Dave Dempsey (2001).

Two documentary films were produced about Hooker Chemical: “The Tragedy of White Lake” produced by Grand Valley State College in 1978, and “This is Not a Chocolate Factory” produced in 2003 by former local resident and filmmaker David Ruck for the Lake Michigan Federation (now the Alliance for the Great Lakes). These may be viewed by visiting the Subject Matter Resource Collection page of the Restoring White Lake website.

Remedial Action Plans (RAPs)

Remedial efforts at the Hooker Chemical site had begun in 1981-82 following inspections by Michigan’s Water Resources Commission in the 1970s and a lawsuit by Michigan’s Attorney General in 1979 demanding cleanup of the site. Chemical operations ceased in 1982. Through a long Corrective Action process, Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) oversaw the investigation and cleanup of this hazardous waste site.

In the fall of 1987, the first Remedial Action Plan for the White Lake Area of Concern (1987 RAP) was released by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) Surface Water Quality Division. In addition to the Occidental (Hooker) Chemical Company property, the 1987 RAP named eight other contaminated sites that likely had contributed to the pollution of the lake. The RAP also laid the groundwork for identifying specific impairments in White Lake that could be measured and remediated to restore the health of the lake. The 1987 RAP recommended specific studies to be done, actions to be taken, and parties to be responsible for carrying out the work.

It also recommended public involvement in the process.

The people of the White Lake area did become involved.

By the time the White Lake Area of Concern Remedial Action Plan: 1995 Update (1995 RAP) was released, the local White Lake Public Advisory Council (WLPAC) had been formed and was actively involved with the MDNR in the decision-making process and the writing of the 1995 RAP. Possible contamination sources had been studied, Beneficial Use Impairments (BUIs) that applied to White Lake had been identified, and work was being done to clean up White Lake.

In 2002 the Remedial Action Plan was again updated (2002 RAP, reprinted in 2005). This update, named White Lake Community Action Plan, prepared by the WLPAC in conjunction with the Muskegon Conservation District (MCD), chronicled the history of White Lake and its cleanup to date. The 2002 RAP also addressed the remaining impairments and included specific actions that the public could take to protect their lake.

The cleanups of the lake proceeded, and as the targeted year for delisting White Lake as an Area of Concern drew near, the MCD, with WLPAC collaboration, conducted an extensive study of the historical contaminated sites to assure that there were no longer any groundwater contaminants threatening residential drinking water in the area. The report, “Assessment of Drinking Water Consumption or Taste and Odor Problems in the White Lake Area of Concern,” (2013 DW Report), provided valuable additional data to supplement the 1987, 1995, and 2002 RAPs for the next section of this report.

Note: the lists of chemicals associated with the major industries listed below can extend to several pages long. For this report I wanted to narrow the list of contaminants to those that were of most concern or were present in the greatest quantities. I used the resources that I will refer to below (the RAPs, the DW Report, NPDES and TRI) for their contaminant lists, assuming that they had selected the most important substances for their reporting.

Groundwater Contaminants

The groundwater contaminants listed as being associated with each of five Industries and four Other Contaminated Sites listed below were found in the 1987 and 1995 Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) and the 2013 DW Report, mentioned above. In some cases, the contaminants were also named on an industry’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit. The NPDES program places legal limits on the discharge of pollutants into surface waters.

The contaminants list for each industry is much longer than the few contaminants listed below: I used the sources named above for this list because the contaminants they mentioned would likely have been those that were of most concern. Substances that are considered to be known or potential carcinogens will appear in bold. the following resources were used to identify carcinogens:

- The Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Carcinogen Listing for TRI Chemicals, citing the list of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) – (“Carcinogenic”, “Probably Carcinogenic”, or “Possibly Carcinogenic to humans”)

- National Toxicology Program (NTP) 15th Report on Carcinogens – (“Known to be…” or “Reasonably Anticipated to be a human carcinogen”)

Note: some substances may not appear on the carcinogens lists because they have not been tested.

Industries (Years of Operation), Groundwater Contaminants of Concern

- Eagle Tanning Works/Whitehall Leather Company/Genesco (1865-2000)

Analysis of 1994 samples from settling ponds and sludge disposal areas detected high concentrations of arsenic, chromium, cobalt, lead, mercury, silver, copper, magnesium, vanadiums and zinc. High concentrations of chromium were especially noted. (1995 RAP, p. 51) - Misco/Howmet/Alcoa Howmet/Arconic (1951-present)

Contaminants documented to have been detected historically in some monitoring wells included tetrachloroethene (tetrachloroethylene), trichloroethylene, cis-1,2-dichloroethene, chloroform, and vinyl chloride. (2013 DW Report, p. 4-5) - Hooker Chemical/Occidental Chemical (1952-1982)

Contaminants of concern in the groundwater included chloroform, carbon tetrachloride, trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene (tetrachloroethylene), hexachlorobutadiene, hexachlorocyclopentadiene, octachlorocyclopentene, and hexachlorobenzene. Hexachloroethane, 1,2-dichlorobenzene, 1,3-dichlorobenzene and 1,4-dichlorobenzene had been observed in some wells at low concentrations. (1995 RAP, p. 48) - E.I. duPont de Nemours/Chemours (1956-1996)

Contaminants limited in their NPDES permit included sulfates, chlorides, trichlorofluoromethane, trichlorotrifluoroethane, fluoride, antimony, carbon tetrachloride, chloroform, methylene chloride (dichloromethane), tetrachloroethylene, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, and trichloroethylene. (1987 RAP, p. 60-61) - Muskegon/Koch Chemical (1975-1991)

Groundwater contaminants of concern detected in monitoring wells in a groundwater plume extending to Mill Pond Creek in 1986 included 1,2-dichloroethane, bis(2-chloroethyl)ether, triethylene glycol dichloride, trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene and chlorobenzene. (1987 RAP, p. 75)

Other Contaminated Sites (approximate year contamination was discovered or confirmed)

- Anderson Road Plume/Tech Cast (1978)

Tetrachloroethylene and trichloroethylene groundwater contamination resulted in residents with private wells being connected to city water. (2013 DW Report, p. 5-6) - Whitehall Municipal Well #3 (1980)

Tetrachloroethylene (PCE) was detected in 1980, and the well was taken offline in 1981. (2013 DW Report, p. 25) - White Lake Landfill and Shellcast (1981)

Landfill contamination may have mingled with that from the Shellcast site. tetrachloroethene (tetrachloroethylene) was detected in a landfill monitoring well that is downgradient from the Shellcast site. (2013 DW Report, p. 6) - Whitehall Wastewater Treatment Facility/Silver Creek site (1984)

Priority pollutants detected in monitoring and observation wells in 1981 and/or 1982 were bis(ethylhexyl)phthalate, vinyl chloride, chloroform, 1,2-dichloroethane, tetrachloroethylene, bis(2-chloroethyl)ether, chloromethane, toluene, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, trichloroethylene, bis(ethylhexyl)ether, trans-1,2-dichloroethylene, and chlorobenzene. (1987 RAP, p. 79-80)

Air Emissions

To understand the impact of air emissions on a community, it is helpful to know about the direction and velocity of prevailing winds. A wind rose gives a view of how wind speed and direction are typically distributed at a particular location, showing the frequency of winds blowing from particular directions. [Natural Resources Conservation Service National Water and Climate Center, United States Department of Agriculture]

Users of the Wind Rose Dataset of the National Water and Climate Center may select their state and then the nearest city to their community to view wind rose GIF images for each month of the year. The plot year for Grand Rapids, Michigan, is 1961. The wind roses for the west Michigan area appear to confirm what residents would suspect: that the prevailing winds for most months are from the south, the southwest, and the west (heading from some major pollution sources toward the north, the northeast and the east – toward the towns of Montague and Whitehall).

The 1987, 1995, and 2005 Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) helped to identify chemicals that are reported to have contributed to groundwater contamination in the White Lake area’s past, but little information on air emissions was found in the RAPs. Therefore I used other sources, such as the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI).

Established in 1987, the TRI, operated by the EPA, tracks certain chemicals that are released by U.S. facilities to the environment. Throughout the history of TRI, batches of chemicals have been added to the List of Toxic Chemicals in 1990, 1991, 1994, 1995 (large batch), 2000, 2011, 2012, 2014-2017, 2019, and 2020 (large batch). As of 2021, the TRI toxic chemical list contains 770 individually listed chemicals and 33 chemical categories.

TRI Reports must be filed by owners and operators of facilities that 1) fall within a TRI-reportable industry sector or are federally-owned or operated; 2) have 10 or more full-time employees; and 3) Manufacture, Process or Otherwise Use (MPOU) a TRI-listed chemical in an amount above the TRI reporting threshold for that chemical during a calendar year. [Factors to Consider, p. 8] If a facility does not meet all these criteria, it is not required to report to TRI. Each reporting facility must submit data for each chemical for which it exceeded an MPOU threshold. During the first two years of TRI-required reporting, the thresholds for reporting chemicals to TRI were 75,000 lbs in 1987 and 50,000 lbs in 1988. Beginning in 1989 and all subsequent years, the threshold for reporting has been 25,000 lbs for TRI reportable chemicals. [Factors to Consider, p. 6]

The data are reported in annual totals of releases (in pounds) per facility and provide no indication of frequency, intensity, or duration of releases.

The TRI datasets may be downloaded for each calendar year since 1987, then sorted by city to locate facilities in Montague and Whitehall that were required to report. The data include details on quantities of chemicals managed through disposal or releases (air, water, and land). In this cancer project report, I mention only the chemicals for which quantities were entered as “Air Emissions” that are labeled as “Fugitive Air” (defined as all releases to air not through a confined air stream), and/or “Stack Air” (defined as confined air streams, such as stacks, vents, ducts or pipes).

Listed below are six White Lake area facilities that reported chemicals to TRI as Fugitive and/or Stack Emissions in TRI’s first three years: 1987, 1988 and/or 1989.

Chemicals in bold are those identified as carcinogens by TRI (citing IARC and NTP carcinogen lists), the NTP’s 15th Report on Carcinogens list, or the ATSDR (citing EPA lists). Some substances may not appear on carcinogens lists because they have not been tested.

- Whitehall Leather Company: ammonia, sulfuric acid, methanol

- Howmet Corp. – Plants 1 & 3: nitric acid, sulfuric acid, cobalt, nickel, aluminum oxide (fibrous forms), aluminum (fume or dust), chromium, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, hydrochloric acid, freon 113, phosphoric acid, sodium hydroxide (solution)

- Howmet Corp. – Plant 4: aluminum (fume or dust), sodium hydroxide (solution), aluminum oxide (fibrous forms), nitric acid, acetone (delisted 1993), 1,1,1-trichloroethane

- Howmet Corp. – Plant 5: aluminum oxide (fibrous forms), nitric acid, freon 113, hydrogen fluoride

- Du Pont Montague Works: acetone (delisted 1993), chloroform, hydrogen fluoride, chlorine, dichloromethane, antimony compounds, methanol, freon 113, hydrochloric acid, 1,1,1-trichloroethane

- Muskegon/Koch Chemical: dichloromethane, xylene (mixed isomers), acetone (delisted 1993), toluene, 1,2-dichloroethane, chlorine, n-butyl alcohol, methanol, methyl isobutyl ketone, hydrazine, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide (solution) (delisted 1988), sulfuric acid, phenol, tetrachloroethylene

Hooker Chemical ceased operations in 1982, and thus does not appear on the TRI lists. Data on air emissions of Hooker/Occidental Chemical were found through searches of archived information stored at the Montague City Hall. This included correspondence from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Air Quality Division (reported on sampling results focused on C-56 detection), the Canonie D’Appolina Waste Isolation Services, Pittsburgh, PA (monitored odors and recommended safety procedures during movement of wastes in 1980-1982), and the Midwest Research Institute (provided a history of the stack and analyzed the safety of the demolition of the stack in 1995) [Hooker/Occidental Archives, Montague City Hall].

- Hooker/Occidental Chemical & Plastics Corp.: Air Emissions information from the above documents included references to hydrogen gas, hydrogen chloride, chlorine gas, hexachlorobutadiene (C-46), hexachlorocyclopentadiene (C-56), octachlorocyclopentene (C-58), hexachlorobenzene (C-66), and mirex (in road dust).

Further inquiries suggest that the production of chlorine using a chlor-alkali process similar to the process used by Hooker can be a source of dioxin-like compounds. [Takasuga et al.]

Delisting of White Lake as an AOC

After 30 years of work by federal, state, and local actors, previously impaired beneficial uses of White Lake had been restored and White Lake was delisted as an AOC in 2014. (See the Delisting Report.) Thereafter, the White Lake Public Advisory Council completed its work as the local group overseeing the cleanup of the lake. A new local group, known as the Chemours Environmental Impact Committee (CEIC, allied with White River Township), organized in 2018 to advocate for the cleanup of the DuPont/Chemours property, which had not yet completed its cleanup operations. As of 2022, CEIC continues to consult with the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) on the cleanup of this former industrial site.

The White Lake Environmental History Project chronicled the history of the pollution and the recovery of White Lake and published the website Restoring White Lake: Exploring White Lake’s Environmental History in 2014. This collection of historical data includes written materials, photos, documentaries, and videos of citizens telling stories of their experiences with the industries and the pollution. A map of contaminated sites and timeline of events, downloadable as a full-sized PDF from the Subject Matter Resource Collection page, illustrates the historical pollution issues and the subsequent restoration efforts.