White Lake Area Cancers

Cancer Diagnosis and Classification

Cancer registrars are certified professionals who participate in ongoing training to stay up to date on coding and all other information needed to maintain a cancer registry. Cancer incidence information is usually organized for the public by topographical site (the body part where the cancer first appeared). A topography code is assigned, which describes the anatomical site of origin of the neoplasm. A morphology code is also assigned, which describes the characteristics of the tumor itself, including its cell type and biological activity.

Participants in this cancer mapping project usually reported the topographical site (for example, “brain”), although they or their death certificate sometimes named their cancer according to their tumor’s morphology (for example, “astrocytoma”).

We did not have the services of a trained cancer registrar, nor did we have access to participants’ medical records to verify cancer types, so when possible I searched public death records of those who were deceased in an attempt to validate the type of cancer.

Researchers have explored the subject of the accuracy and usefulness of the cause of death reported on the death certificate for studies in which resources were not available to gain access to medical records and have found acceptable agreement between the underlying cause of death from death certificates when compared with medical records and population-based cancer registry data.

Although some caveats were mentioned (such as reduced accuracy in death certificates of patients with more than one primary cancer diagnosis, and a finding that nonphysician coroners had lower accuracy rates compared with physicians), I learned that it has been shown to be acceptable to use death records to verify diagnoses when medical records are not available.

Throughout the survey period we attempted to verify that the cancers being reported were primary cancers, not cancers that had originated from another site. When participants had two or more cancers, I tried to verify that each was a primary cancer.

Organizing Cancer Types into Groups

To organize our participants’ cancers into groups, I relied on the following National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) online information sources: 1) Cancer Types, 2) Cancer Stat Facts, 3) Training Modules, and 4) ICD-O-3 SEER Site/Histology Validation Lists. I supplemented these with information from cancer type-specific websites when needed.

For the purposes of this project, I defined some groups in a unique way in order to be able to include all participants, including those with rare cancers, within a manageable number of categories.

Rare Cancers

Many of the White Lake area residents on our list had rare cancers. Rare cancers present challenges to patients and their families: research dollars tend to be spent on common cancers, less information is available on what to expect in terms of prognosis, fewer treatment protocols have been tested, economies of scale favor drugs with widespread potential use, and local cancer incidence tables available to the public often report only the common cancers, leaving the person with a rare cancer wondering if their own cancer was counted.

As one patient of a rare cancer describes it, “It is a lonely cancer because you are robbed of people going through the same thing” (RARECARENet).

A paper by the European Parliament, Background Note on Paediatric and Rare Cancers (2021), notes additional barriers for people with rare cancers:

“Diagnosis for rare and paediatric cancers can be delayed due to (i) the presence of perhaps only negligible symptoms, (ii) the lack of associated risk factors, and (iii) the fact that patients developing rare cancers are not from the usual population groups considered as “at risk of cancer” (p. 4).

Keat et al. (2013) add that “the average outcome for patients with a rare cancer is inferior to those with more common cancers. One factor contributing to this is the lack of evidence upon which to base treatment, so in an attempt to address this issue, the International Rare Cancers Initiative (IRCI) was established early in 2011” (par. 3).

RARECARENet builds on the previous project, Surveillance of Rare Cancers in Europe (RARECARE: approximately 1995-2007), which estimated that around 4 million people in the European Union are affected by rare cancers, defined as fewer than 6 per 100,000 per year. Despite the rarity of each of the 186 identified rare cancers, rare cancer diagnoses in Europe taken together represent about 22% of all cancer cases diagnosed annually.

In the U.S., Greenlee et al. (2010) compared rare and non-rare incidence rates (using a previous definition of rare as being fewer than 15 cases per 100,000 per year) and found that 60 of 71 cancer types were rare, accounting for 25% of all adult tumors. They concluded that “collectively, rare tumors account for a sizable portion of adult cancers” and they noted the growing data-collection sources that are useful for “research on rare cancers, potentially leading to a greater understanding of these cancers and eventually to improved treatment, control, and prevention” (par. 4).

The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER) has submitted an updated list of rare cancers (2020, based on data up to 2018). There are more than 300 identifiable cancers on the updated list.

Based on the RARECARE project, researchers in the U.S. and Europe, including Gatta, G. et al. (2011), Casali and Trama (2020), and Botta, L. et al. (2020), have used the definition of “rare” as an incidence of less than 6 per 100,000 per year. A significant proportion, 20%-24%, of all patients diagnosed with cancer are rare according to this definition.

Casali and Trama state it candidly:

“[W]e hope that … improved awareness of the problems posed by rare cancers may contribute to improving quality of care in a large group of patients with cancer who may be discriminated against just because of the low frequency of their disease” (p. 6).

| Cancer Groups: 20 Adult cancer groups (age 20+) One Childhood & Adolescent group (age range 0-19) |

Range of years members of this cancer group were diagnosed |

# of cancers diagnosed in this cancer group |

# of cancers diagnosed while participant was a full-time resident of WL area |

# of cancers diagnosed after participant moved away from WL area |

# of cancers diagnosed while participant was a part-time resident of WL area |

| Bladder |

1970-2010 |

42 |

33 |

7 |

2 |

| Brain & Nervous System |

1957-2013 |

32 |

22 |

10 |

0 |

| Breast |

1950-2013 |

218 |

141 |

66 |

11 |

| Colorectal |

1943-2011 |

96 |

78 |

16 |

2 |

| Gynecologic |

1953-2013 |

68 |

48 |

18 |

2 |

| Head & Neck |

1971-2010 |

36 |

27 |

8 |

1 |

| Kidney & Ureter |

1971-2010 |

22 |

17 |

5 |

0 |

| Leukemia |

1960-2010 |

31 |

23 |

8 |

0 |

| Lung |

1972-2012 |

172 |

140 |

28 |

4 |

| Lymphoma |

1951-2012 |

61 |

42 |

17 |

2 |

| Melanoma & Metastatic Skin |

1971-2011 |

40 |

23 |

14 |

3 |

| Multiple Myeloma |

1967-2012 |

23 |

20 |

2 |

1 |

| Neuroendocrine & Carcinoid |

1981-2013 |

9 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

| Pancreatic & Biliary Tract |

1950-2013 |

48 |

39 |

9 |

0 |

| Prostate |

1967-2012 |

94 |

74 |

17 |

3 |

| Sarcoma |

1959-2012 |

32 |

22 |

9 |

1 |

| Testicular |

1967-2009 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

| Thyroid |

1970-2012 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

0 |

| Upper Gastrointestinal Tract |

1957-2010 |

30 |

24 |

5 |

1 |

| Cancer Unknown Primary Site |

1979-2012 |

20 |

17 |

3 |

0 |

| Childhood & Adolescent (0-19) |

1957-2009 |

21 |

18 |

2 |

1 |

| Total Number of Cancers |

1943-2013 |

1,115 |

823 |

257 |

35 |

| Percentage |

— |

— |

74% |

23% |

3% |

Cancer Type (number of participants with this type): cancer diagnoses that I included within this cancer type

(nos = not otherwise specified by the participant or death certificate)

Bladder (42): bladder nos, squamous cell, transitional cell, verrucous carcinoma of bladder. (One person had 2 primary bladder cancer types.)

Brain and Nervous System (32): brain nos, glioma (glioblastoma, astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma), cerebellar medulloblastoma, spinal cord tumor; benign brain nos, acoustic neuroma, meningioma.

Breast (218): many descriptions, including breast nos, ductal or lobular, in situ (DCIS) or invasive, carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, BRCA gene positive or negative, HER2+ or HER2-, medullary carcinoma, phyllodes tumor, pigmented Paget’s disease, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma, inflammatory, and male breast.

Colorectal (96): colorectal, colon, rectal, appendiceal.

Gynecologic (68): uterine, ovarian, cervical, vaginal, vulvar, fallopian tube, mixed mesodermal tumor of uterus, dysgerminoma of ovary, clear cell adenocarcinoma of ovary, multiple primary (one person had two types of gynecologic cancers).

Head & Neck (36): head & neck nos, laryngeal, mouth, salivary gland, sinus & nasal cavity, throat & oropharynx, tongue, tonsil.

Kidney & Ureter (22): kidney nos, renal cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, reno-urothelial carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma of ureter.

Leukemia (31): leukemia nos, acute leukemia nos, acute lymphocytic, acute myeloid, chronic lymphocytic, chronic myeloid, hairy cell, large granular lymphocytic.

Lung (172): lung nos, non-small cell lung cancer nos, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, small cell (oat cell) lung cancer, clear cell.

Lymphoma (61): Hodgkin, lymphoma nos (presumed to be non-Hodgkin), non-Hodgkin nos, B-cell, large B-cell, large cell, follicular, mantle cell, anaplastic T-cell, small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Melanoma & Metastatic Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers (40): melanoma of the skin, metastatic non-melanoma skin cancers, melanoma of the eye.

Multiple Myeloma (23): multiple myeloma, multiple myeloma with plasmacytoma.

Neuroendocrine & Carcinoid (9): neuroendocrine nos; neuroendocrine pancreas; pituitary adenoma; carcinoid nos; carcinoid liver, colon, lung, breast, small intestine.

Pancreatic & Biliary Tract (48): pancreatic, liver, bile duct, gallbladder.

Prostate (94): prostate.

Sarcoma (32): soft tissue sarcoma nos, mesothelioma, Ewing sarcoma, bone nos (jaw), chondrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, uterine sarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma, subcutaneous giant cell tumor, histiocytoma, hemangioendothelioma, peripheral neuroepithelioma, malignant schwannoma, carcinosarcoma.

Testicular (10): testicular, seminoma.

Thyroid (10): thyroid nos, papillary, follicular, adenocarcinoma.

Upper Gastrointestinal Tract (30): esophagus, stomach, small intestine, duodenal.

Cancer of Unknown Primary (20): metastatic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, large cell, non-small cell, signet ring cell, pseudomyxoma peritonei.

Childhood & Adolescent (21): bladder, bone (osteosarcoma), brain (brain nos, glioma), kidney (Wilms tumor), leukemia (leukemia nos, acute lymphatic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia), liver (hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular), lymphoma (Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma), testicular, thyroid (papillary thyroid).

Residence at Diagnosis: IN, AWAY, and PART TIME

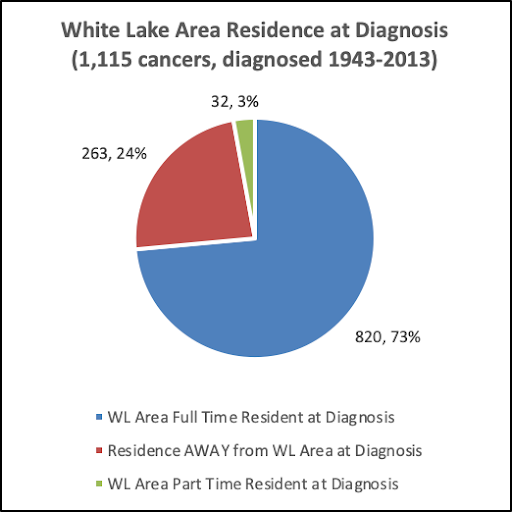

The pie chart below illustrates the numbers and percentages of the 1,051 participants who were diagnosed with 1,115 cancers while living full time in the White Lake area, those who were diagnosed after moving away, and those who were part-time or seasonal residents the year they were diagnosed.

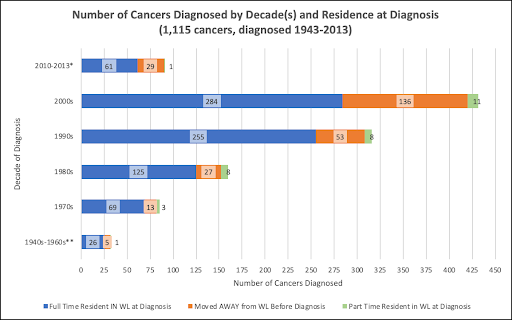

When were the 1,115 cancers diagnosed? How many participants were full-time residents, how many had moved away from the White Lake area prior to diagnosis, and how many were part-time residents at diagnosis?

* The survey period initially ended in 2012. It was extended to July of 2013, resulting in a few more surveys being completed. The reported cancer diagnoses per year were: 47 in 2010, 27 in 2011, 12 in 2012 and 5 in 2013.

** Cancers diagnosed in the 1940s-1960s were: 2 in the 1940s, 11 in the 1950s, 19 in the 1960s.

The greater number of cancer diagnoses in the 2000s may attest to the concerns expressed by citizens of the White Lake area that resulted in the 2009 launch of this cancer mapping project. Other possibilities are that more people might have been likely to choose to participate in this voluntary project when their cancer had been more recently diagnosed or, as is often pointed out, more people may be diagnosed in more recent years due to improved screening and early detection of cancers.

Or, was there actually a greater-than-expected number of cancers diagnosed in White Lake area residents during the early 2000s? Recall that environmental toxins were still present in the 1980s and 1990s, if that was a contributing factor. Cleanup in some areas had begun but was not near completion.

The problem that is repeatedly mentioned as a liability in reporting on cancer incidence statistics, “Counts and rates are calculated based on residential address at time of diagnosis. No information is available on prior residences” carries with it an associated problem. Statisticians do not know how long a person has been living at the residence at which they were diagnosed.

The residence-at-diagnosis information shown in the above-mentioned charts does not give us a sense of how long participants had lived at their address before being diagnosed or, if they had moved away, how long they had been away before being diagnosed.

I tried to address this issue and was confronted with many challenges. I could look at each individual and calculate how many years they had lived in the White Lake area, versus how many years they had lived outside of the area prior to their diagnosis, but when I tried to summarize this for a group of people, the information was not useful because we don’t know how long the latency period would have been for their types of cancer. I will address the Latency Challenge later in this report.